'Manifesto (I Speak For My Difference)' by Pedro Lemebel

Manifiesto (Hablo por mi diferencia) por Pedro Lemebel

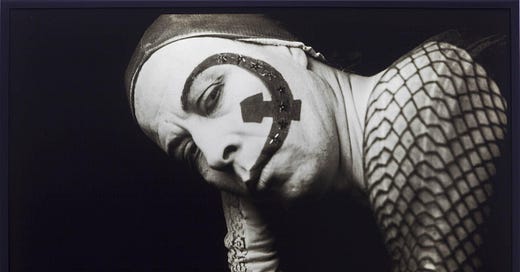

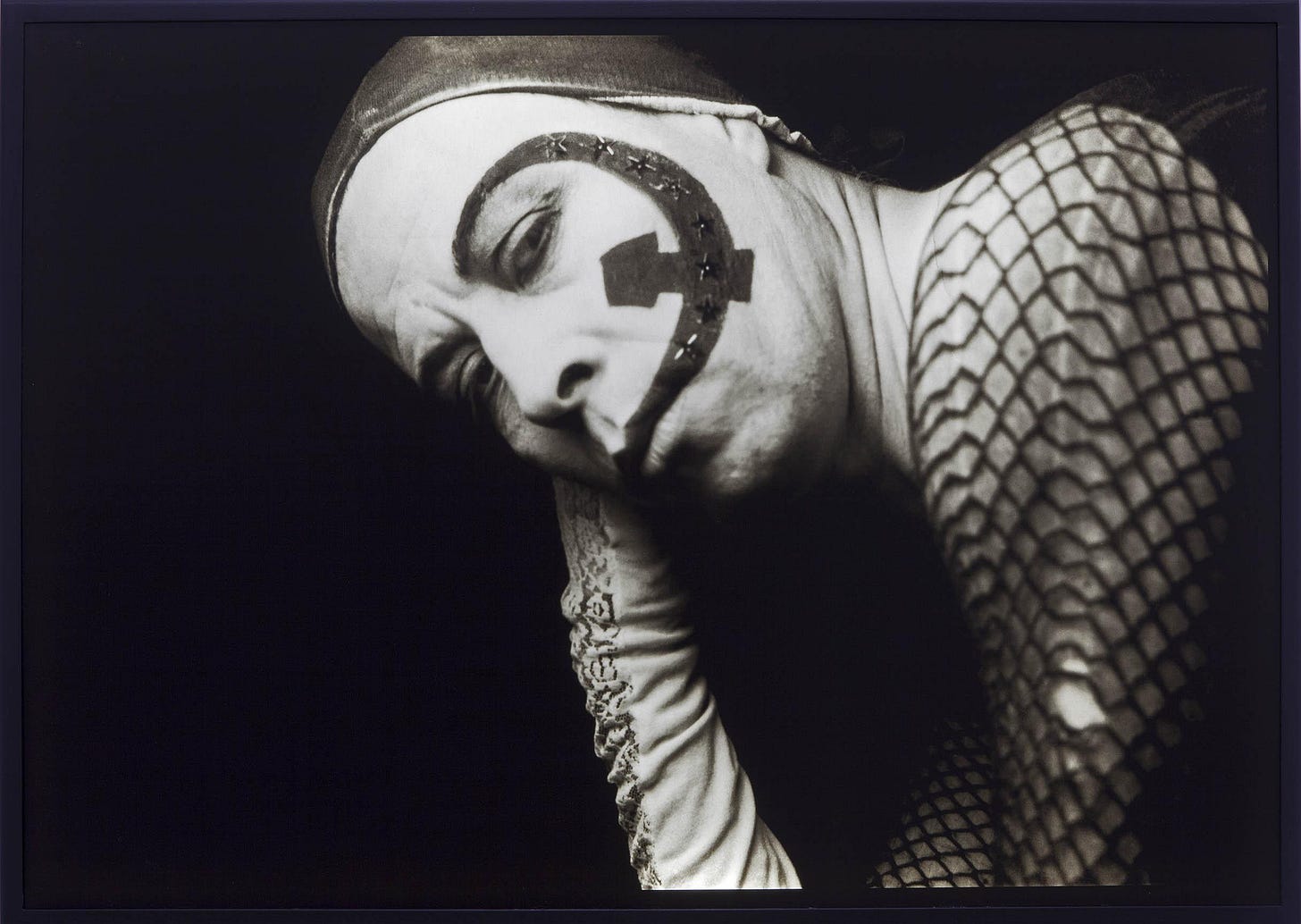

Pedro Lemebel (1952–2015) was a Chilean artist, writer, and queer revolutionary. They (Lemebel referred to themselves using both feminine and masculine gendered language, so I use gender-neutral pronouns to avoid confusion) first made their mark on Chilean literature through a series of performances and readings made in the 1980s. Their writings (including poetry, short stories, and non-fiction pieces) were known for their boldly queer and provocative stance, as well as for their ability to commemorate the beauty and the grit of working-class queer life in Chile.

Here I publish one of Lemebel’s most well-known (but heretofore untranslanted into English) poems, known as his Manifiesto or ‘Hablo por mi diferencia’. In 1986, there was a large gathering of left-leaning opposition groups in the Mapocho Station of Santiago. It was here that Lemebel would make their defiant entry into Chile’s literary culture, dressed in high heels and with a hammer and sickle dolled onto their face. It is this context, of an intransigent public intervention against the established left in Chile, that the poem should be read. Although the Soviet Union had abolished the criminalization of homosexuality after the October Revolution, the ascent of Stalin led to the country becoming more conservative, with the recriminalization of homosexuality being passed by decree in 1933. Thus, most of the revolutionary groups of the 20th century, being predominantly Marxist-Leninist, followed the Soviet homophobic line.

This led Lemebel to experience a doubling of their alienation: firstly, being alienated by the violently conservative military junta that governed Chile at the time, and secondly, being alienated by its similarly homophobic opposition. To reactionary and revolutionary alike, Lemebel was seen as swimming against the current. Manifesto thereby is Lemebel’s attempt to carve out their own space in this movement, a space which was as revolutionary as it was queer. Striking out in a tragicomic vernacular, this poem is part-chronicle, part auto-biography and part call to action. It is Lemebel speaking on behalf of their difference, rejecting attempts to construe their alterity as at odds with serious political activism, and celebrating it as its own source of praxis.

To achieve this, Lemebel draws own their own idiomatic language, one that developed its eccentricity through its inheritance of queer and working-class dialects. Their writing expresses chilensis, a term that Chilean people use to describe their particularly brusque and crude adoption of the Spanish language (filtered in part through various Mapuche loan words). Thus, one of my primary aims was capturing the informal and idiomatic language of the poem without lapsing too much into domestication. To compliment this, I have also included a series of footnotes to add context when needed.

Thank you to Chris Poole for his insightful comments, as always.

Hablo por mi diferencia

No soy Pasolini pidiendo explicaciones No soy Ginsberg expulsado de Cuba No soy un marica disfrazado de poeta No necesito disfraz Aquí está mi cara Hablo por mi diferencia Defiendo lo que soy Y no soy tan raro Me apesta la injusticia Y sospecho de esta cueca democrática Pero no me hable del proletariado Porque ser pobre y maricón es peor Hay que ser ácido para soportarlo Es darle un rodeo a los machitos de la esquina Es un padre que te odia Porque al hijo se le dobla la patita Es tener una madre de manos tajeadas por el cloro Envejecidas de limpieza Acunándote de enfermo Por malas costumbres Por la mala suerte Como la dictadura Peor que la dictadura Porque la dictadura pasa Y viene la democracia Y detrasito el socialismo ¿Y entonces? ¿Qué harán con nosotros, compañeros? ¿Nos amarrarán de las trenzas en fardos con destino a un sidario cubano? Nos meterán en algún tren de ninguna parte Como en el barco del general Ibáñez Donde aprendimos a nadar Pero ninguno llegó a la costa Por eso Valparaíso apagó sus luces rojas Por eso las casas de caramba Le brindaron una lágrima negra A los colizas comidos por las jaibas Ese año que la Comisión de Derechos Humanos no recuerda Por eso, compañero, le pregunto ¿Existe aún el tren siberiano de la propaganda reaccionaria? Ese tren que pasa por sus pupilas Cuando mi voz se pone demasiado dulce ¿Y usted? ¿Qué hará con ese recuerdo de niños Pajeándonos y otras cosas En las vacaciones de Cartagena? ¿El futuro será en blanco y negro? ¿El tiempo en noche y día laboral sin ambigüedades? ¿No habrá un maricón en alguna esquina desequilibrando el futuro de su hombre nuevo? ¿Van a dejarnos bordar de pájaros las banderas de la patria libre? El fusil se lo dejo a usted Que tiene la sangre fría Y no es miedo El miedo se me fue pasando De atajar cuchillos En los sótanos sexuales donde anduve Y no se sienta agredido Si le hablo de estas cosas Y le miro el bulto No soy hipócrita ¿Acaso las tetas de una mujer no lo hacen bajar la vista? ¿No cree usted que solos en la sierra algo se nos iba a ocurrir? Aunque después me odie Por corromper su moral revolucionaria ¿Tiene miedo que se homosexualice la vida? Y no hablo de meterlo y sacarlo Y sacarlo y meterlo solamente Hablo de ternura, compañero Usted no sabe Cómo cuesta encontrar el amor En estas condiciones Usted no sabe Qué es cargar con esta lepra La gente guarda las distancias La gente comprende y dice: Es marica pero escribe bien Es marica pero es buen amigo Súper-buena-onda Yo no soy buena onda Yo acepto al mundo Sin pedirle esa buena onda Pero igual se ríen Tengo cicatrices de risas en la espalda Usted cree que pienso con el poto Y que al primer parrillazo de la CNI Lo iba a soltar todo No sabe que la hombría Nunca la aprendí en los cuarteles Mi hombría me la enseñó la noche Detrás de un poste Esa hombría de la que usted se jacta Se la metieron en el regimiento Un milico asesino De esos que aún están en el poder Mi hombría no la recibí del partido Porque me rechazaron con risitas Muchas veces Mi hombría la aprendí participando En la dura de esos años Y se rieron de mi voz amariconada Gritando: Y va a caer, y va a caer Y aunque usted grita como hombre No ha conseguido que se vaya Mi hombría fue la mordaza No fue ir al estadio Y agarrarme a combos por el Colo Colo El fútbol es otra homosexualidad tapada Como el box, la política y el vino Mi hombría fue morderme las burlas Comer rabia para no matar a todo el mundo Mi hombría es aceptarme diferente Ser cobarde es mucho más duro Yo no pongo la otra mejilla Pongo el culo, compañero Y ésa es mi venganza Mi hombría espera paciente Que los machos se hagan viejos Porque a esta altura del partido La izquierda tranza su culo lacio En el parlamento Mi hombría fue difícil Por eso a este tren no me subo Sin saber dónde va Yo no voy a cambiar por el marxismo Que me rechazó tantas veces No necesito cambiar Soy más subversivo que usted No voy a cambiar solamente Porque los pobres y los ricos A otro perro con ese hueso Tampoco porque el capitalismo es injusto En Nueva York los maricas se besan en la calle Pero esa parte se la dejo a usted Que tanto le interesa Que la revolución no se pudra del todo A usted le doy este mensaje Y no es por mí Yo estoy viejo Y su utopía es para las generaciones futuras Hay tantos niños que van a nacer Con una alíta rota Y yo quiero que vuelen, compañero Que su revolución Les dé un pedazo de cielo rojo Para que puedan volar.

I Speak For My Difference

I am not Pasolini asking for explanations

I am not Ginsberg expelled from Cuba

I am not a fag disguised as a poet

I don’t need a disguise

Here is my face

I speak for my difference

I defend what I am

And I am not so strange

I hate injustice

And I don’t trust this democratic dance

But don’t talk to me about the proletariat

Because being poor and a faggot is worse

You gotta be rough to bear it

It’s crossing the street when you see those lads on the corner1

It’s a father that hates you

Because his one and only son has a limp wrist

It’s having a mother with hands cut by chlorine

Aged by cleaning

Cradling you when you’re sick

Because of bad habits

Because of bad luck

Like the dictatorship

Worse than the dictatorship

Because dictatorships end

And then comes democracy

And right behind it socialism too

And so?

What will they do with us, comrades?

Will we be tied by our braids into bundles

bound for a Cuban AIDS sanitorium?2

They’ll put us on some train to nowhere

Like on General Ibáñez’s ship3

Where we learned to swim

But none of us made it to shore

Because of that Valparaíso dimmed its red lights

Because of that the whorehouses

Poured out a single black tear

For those fruits feasted on by crabs4

That year the Commission of Human Rights

doesn’t remember

Because of that, comrade, I’m asking you

Does the Siberian train that

reactionaries decry still exist?

That train that passes before your eyes

When my voice starts to get too sweet

And you?

What will you do with that childhood memory

Of us stroking our cocks together (among other things)

While on holiday in Cartagena?

Will the future be in black and white?

Will the difference between night time

and the working day always be clear?

Won’t there be a faggot on some corner

Throwing the future of your new man off balance?5

Will they let us embroider birds

on the flags of our free homeland?

I leave the rifle to you

Who is cold-blooded

And it’s not fear

I lost my fear

Of dodging knives

In the seedy basements where I spent my time

And don’t feel attacked

If I speak to you of these things

And check out your bulge

I’m not a hypocrite.

Don’t a woman’s tits

Make you lower your gaze?

Don’t you think

That alone in the mountains

Something would happen between us?

Even if you hate me afterwards

For corrupting your revolutionary morals.

Are you scared I’ll homosexualize your life?

And I’m not just talking about putting it in

& taking it out & taking it out & putting it in

I’m talking about tenderness, comrade

You don’t know

How much it costs to find love

In these conditions

You don’t know

What it’s like to carry this leprosy

People keep their distance

People understand and say:

He’s a fag but he writes well

He’s a fag but he’s a good friend

Real-good-vibes

But I’m not good vibes

I accept the world

Without asking for those good vibes

But either way they laugh

There are scars of laughter on my back

You say I think with my ass

And that with the first shock of the electric prod6

I’d let it all slip

You don’t know that I never learnt

My manhood in the barracks

The night taught me my manhood

Behind a post

That manhood you boast of

Was drilled into you in boot camp

By a murderous pig

Like the ones still in power

I didn’t get my manhood from the party

Because they rejected me with sniggers

More than once

I learnt my manhood participating

In the struggle of those years

And they laughed at my faggy voice

Chanting: And it’s gonna fall, and it’s gonna fall7

And although you shout like a man

You’ve brought nothing down

My manhood was the gag

It wasn’t going to the stadium

And getting into scraps for Colo-Colo

Football is another form of repressed homosexuality

Like boxing, politics, and wine

My manhood was biting down on my tongue

Eating my rage so I didn’t kill the whole world

My manhood is accepting myself as different

Being a coward is much more difficult

The only other cheek I’ll turn,

Comrade, is on my ass

And that is my vengeance

My manhood waits patiently

For the chauvinists to get old

Because at this stage of the game

The left is trading its limp ass

In parliament

My manhood was difficult

That’s why I won’t get on this train

Without knowing where it’s going

I won’t change for Marxism

Which rejected me so many times

I don’t need to change

I’m more subversive than you

I won’t change just

Because of the rich and the poor

Give me a break

I also wont change because capitalism is unjust

In New York fags kiss on the street

But I’ll let you chew on that

You who are so interested

In the revolution not rotting away

To you I leave this message

And this is not for me

I am old

And your utopia is for those who are to come

There are so many children who will be born

With a broken wing

And I want them to soar, comrade

I want your revolution

To give them a piece of red sky

So they can fly.

In the Spanish text Lemebel refers to machitos, which is the plural diminutive form of macho. I felt that ‘lads’ was best in capturing the sense of a chauvinistic young man.

Cuba’s response to the AIDS crisis was to quarantine indefinitely those who tested positive for HIV. This was, effectively, life-imprisonment. So, while the reference to Cuba might gloss as a positive, it is in fact another representation of the betrayal of queer people by revolutionary movements at the time.

Carlos Ibáñez del Campo (1877-1960) was dictator (1927-1931) and president (1952-1958) of Chile. In the 1930s, General Ibáñez invited prominent gay men and left-wing militants onto a ship in Valparaíso, only to sink it once it was out at sea, killing all aboard.

Here Lemebel speaks of colizas comidos by crabs. A glossary that Lemebel created for one of his works claims that coliza is a informal term for a gay man and (more routinely) a type of bread that is commonly eaten in Chile. Translating colizas as ‘fruits’ (which is admittedly an archaic term) allows me to retain the gastronomic roots of the term while also allowing the alliteration to occur: ‘fruits feasted on’ matching colizas comidos.

A reference to the New Soviet man.

The Spanish reads: Y que al primer parrillazo de la CNI. The CNI, short for Centro Nacional de Informaciones or National Information Center, was Chile’s intelligence agency - akin to the CIA - during the military dictatorship. They were responsible for the persecution, kidnapping, torture, murder and disappearance of political opponents. The parrillazo was a type of electric prod used by the CNI to extract information for prisoners during torture.

A popular political chant at the time, referring to the military junta.

Hola! Cómo puedo contactarte? me gustaría citar tu traducción para una plática en Helsinki.

This is the most beautiful thing l have read in a long time. It is my birthday today, I view this a gift from the ancestors. Thank you. 💐